The Hunter and the Hunted

Through the Periscope of U-20

The Celtic Sea, May 7, 1915. 1:20 PM. Under the rolling grey surface of the Atlantic, the world was silent, pressurized, and smelling of diesel and sweat. Inside the steel belly of the German submarine U-20, Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger adjusted the periscope. For days, the fog had been their enemy, blinding them, but now the sun had burned through the mist, revealing a glassy, calm ocean.

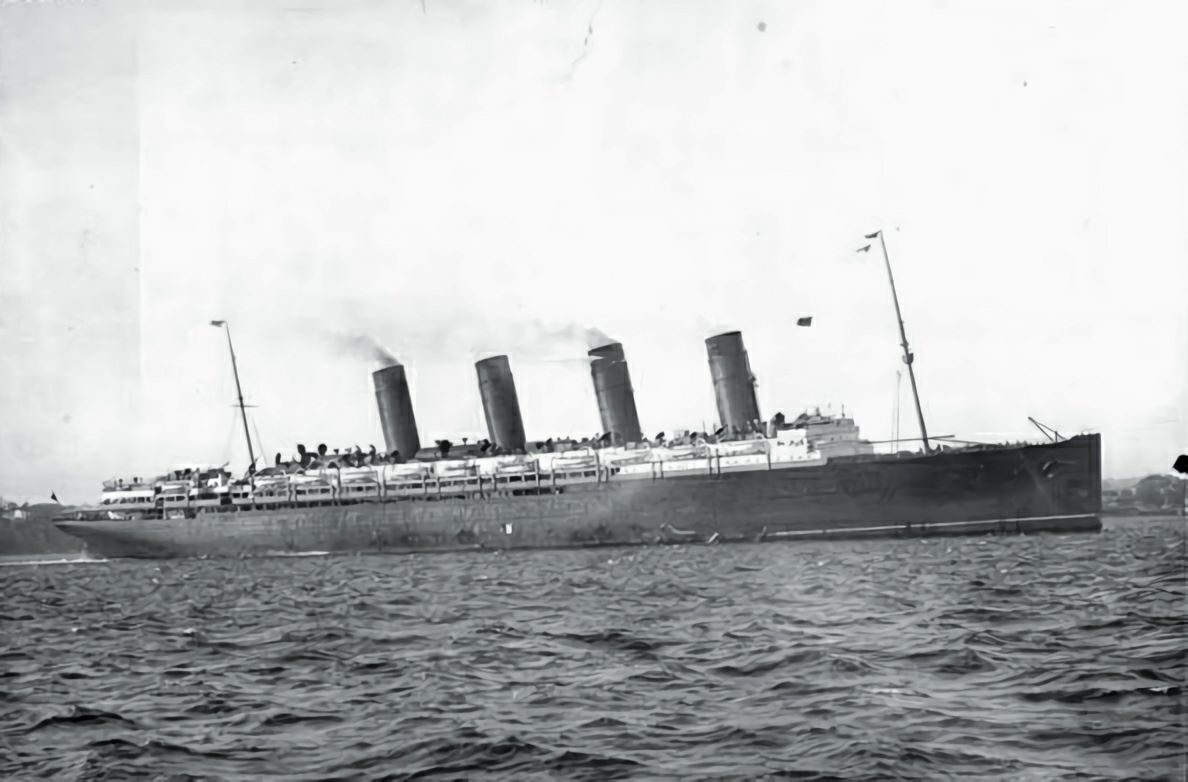

Through the optics, a shape coalesced against the horizon. It was not a merchant scow or a naval destroyer. It was a city. Four massive funnels, painted in the red and black livery of the Cunard Line, smoked aggressively into the clear sky. It was the RMS Lusitania.

Schwieger did not hesitate. There was no radio check, no warning shot across the bow, no adherence to the old "Cruiser Rules" that mandated passengers be allowed to disembark before a ship was sunk. Those rules belonged to a century that was rapidly dying. He tracked the leviathan’s speed—estimated at 18 knots—and calculated the intercept angle.

"Fire G," he ordered.

The submarine shuddered as the single G-type torpedo left the tube. The crew of the U-20 waited. The "torpedo run" is a singular agony in submarine warfare—a suspended breath between the decision to kill and the act of killing. For thirty-five seconds, the weapon knifed through the water, leaving a streak of bubbles in its wake. On the surface, the Lusitania continued her majestic, oblivious glide toward Liverpool, carrying 1,959 souls and a secret that would eventually drag the United States into the First World War.

Then, the silence broke. A dull, concussive thud vibrated through the hull of the U-20. Through the periscope, Schwieger watched water and debris erupt from the liner’s starboard side, just behind the bridge. But what happened next shocked even the German hunter. A second, far more violent explosion ripped the ship apart from the inside, sending a geyser of steam, coal dust, and smoke high above the funnels. The great ship stopped dead in the water and immediately began a terrifying, unnatural roll to starboard. The sinking of the Lusitania had begun.

The Greyhound of the Seas: Hubris Before the Fall

A Palace of Steam and Velvet

To understand the violence of her end, one must understand the majesty of her life. The Lusitania was not merely a ship; she was a floating statement of British imperial dominance. Launched in 1906, she was the "Greyhound of the Seas," the holder of the Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic crossing. She was a technological marvel powered by revolutionary steam turbine engines that could drive her 31,550 tons at speeds exceeding 25 knots—faster than any German submarine of the era.

Inside, she was a palace. Her first-class lounge was adorned with mahogany panels and stained glass; her dining saloon was a double-tiered masterpiece of white plasterwork and gold leaf, where passengers dined on caviar and oysters under an immense dome. There were electric elevators, a novelty that fascinated the Edwardian elite, and nursery rooms for the children.

The passengers boarding in New York on May 1st, 1915, were wrapped in a blanket of hubris. They believed that civilization protected them. They believed that the sheer speed of the Lusitania made her invulnerable. They were wrong. They were stepping onto a target that had been marked for death before the gangplank was even lowered.

The German Warning Notice of 1915

The tragedy was not without a prelude. In a move of chilling transparency, the Imperial German Embassy in Washington, D.C., had placed a notice in fifty American newspapers on the morning of the Lusitania’s departure. It appeared directly next to the Cunard advertisements.

NOTICE!TRAVELERS intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles... in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travelers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSYWashington, D.C., April 22, 1915.

On the decks of the Lusitania, the warning was the subject of nervous laughter. Passengers dismissed it as a bluff or assumed the Royal Navy would escort them through the danger zone. The idea that a passenger liner—a civilian vessel—would be torpedoed without warning was inconceivable to the Edwardian mind. It was "un-sportsmanlike." It was "piracy." It was a failure to realize that the nature of war had fundamentally changed.

Captain William Turner and the Admiralty’s Silence

Captain William Turner was a man of the old school—gruff, taciturn, and deeply experienced. Yet, as the Lusitania approached the southern coast of Ireland, Turner was operating in an intelligence vacuum.

The British Admiralty knew U-20 was in the area. They had tracked its radio signals. They knew Schwieger had already sunk two steamers, the Earl of Lathom and the Candidate, in the days prior. Yet, inexplicably, no specific warning was sent to Turner detailing the precise location of the submarine. Even more damning was the absence of the promised escort. The cruiser Juno, which was supposed to meet the Lusitania, had been recalled to Queenstown (now Cobh) without Turner being informed.

Turner has often been blamed for slowing down and for taking a predictable bearing near the Old Head of Kinsale to check his position. But the true failure lay in London. The Lusitania was a sitting duck, stripped of her speed by fog and fuel conservation orders, and stripped of her protection by an Admiralty that seemed paralyzed—or, as conspiracy theorists would later suggest, calculating.

The Eighteen Minutes: The Sinking of the Lusitania

Impact: The Torpedo Strike

At 2:10 PM, the torpedo struck the starboard side, between the third and fourth funnels. The impact was deafening, but it was not immediately catastrophic. The warhead tore open the steel plates, flooding the starboard coal bunkers. Passengers enjoying their post-lunch tea felt the ship shudder violently, "as if it had hit a stone wall."

If this had been the only damage, the Lusitania likely would have survived, or at least sunk slowly enough to evacuate everyone. She was designed with longitudinal bulkheads to contain flooding. But then came the mystery that haunts the wreck to this day.

The Second Explosion: A Mystery in Coal and Cordite

Moments after the torpedo hit, a second, much larger explosion erupted from deep within the bowels of the ship. This was the death blow. The Lusitania second explosion theory remains the most contentious aspect of the disaster.

Survivors described a "deep, rumbling roar" that shook the ship from keel to masthead. A column of steam and debris shot upward, destroying lifeboat number 5. The electricity failed almost immediately, plunging the interior of the ship into darkness. The hydraulic power to the steering gear was severed, locking the rudder and forcing the ship into a wide, uncontrollable turn.

What caused this second blast? The German government immediately claimed it was proof the ship was carrying illegal munitions. The British Admiralty claimed it was a coal dust explosion. But coal dust explosions usually require an open flame and a specific suspension of dust in the air—conditions that were unlikely in the full bunkers. The violence of the second explosion blew the bottom out of the ship. The "Greyhound" was no longer floating; she was being dragged down.

The List and the Lifeboat Disaster

The Titanic took two hours and forty minutes to sink, staying relatively level for much of that time. The Lusitania gave her passengers no such grace. Within minutes, she developed a severe 15-degree list to starboard, which rapidly increased to 25 degrees.

This list created a geometric nightmare for the crew launching the lifeboats.

- On the Port Side: The boats swung inward, crashing against the railing and the deck houses. Passengers who attempted to board them were often crushed or spilled into the sea as the boats snagged on the ship’s rivets and overturned.

- On the Starboard Side: The boats swung too far out. The gap between the deck and the boat was six feet or more, terrifying passengers who had to jump.

Chaos reigned. The ship was moving forward while sinking, causing lifeboats that did hit the water to be dragged under the propellers or capsized by the ship’s wake. Of the 48 lifeboats on board, only six were successfully launched. The rest were dragged down with the ship or floated away upside down.

Portraits of Tragedy: The Human Cost

The Death of Alfred Vanderbilt

Amidst the screaming and the screeching of tearing metal, there were moments of quiet, devastating heroism. Alfred Vanderbilt, the 37-year-old American multimillionaire, was one of the richest men on board. He was a sportsman, a lover of horses, and a man who had narrowly missed traveling on the Titanic three years prior.

Witnesses reported seeing Vanderbilt on the deck, calm and collected. He was wearing a lifebelt. A woman approached him, terrified and without one. Without hesitation, Vanderbilt removed his own lifebelt and strapped it onto her. He then turned to his valet and began helping other children into the few remaining boats. He made no attempt to save himself. As the water washed over the promenade deck, Alfred Vanderbilt stood by the rail, a final avatar of a code of chivalry that was drowning along with the ship. His body was never found.

The Massacre of the Innocents

If Vanderbilt represented the loss of the elite, the steerage and nursery classes represented the "massacre of the innocents." Of the 129 children on board, 94 died. Of the 39 infants, 35 perished.

The image that would galvanize the world was not of the ship itself, but of the aftermath in Queenstown, where the bodies were laid out in makeshift morgues. Rows of small white coffins. The loss of these children became the emotional core of the tragedy. It stripped the Germans of any moral high ground. They hadn't just sunk a ship; they had murdered babies. This "baby killer" narrative would be weaponized with lethal efficiency by British propaganda.

The Propaganda War: Weaponizing the Dead

The "Lusitania Medal" and German Celebration

In a spectacular public relations blunder, a Munich medalist named Karl Goetz created a commemorative medal to mark the sinking. The Goetz Medal was intended to be satirical, criticizing the British for using civilians as human shields for munitions. It depicted the Lusitania sinking under the weight of guns and airplanes, with a skeleton selling tickets at the Cunard office.

However, the medal carried the wrong date—May 5th, instead of May 7th. British Intelligence seized upon this error. They mass-produced replicas of the medal and distributed them worldwide, claiming it proved the sinking was premeditated days in advance and that the Germans were celebrating the death of civilians.

Turning the Tide of Public Opinion

The reaction was visceral. Anti-German riots broke out in London and Liverpool. Shops owned by German immigrants were ransacked. But the most important audience was across the Atlantic.

While President Woodrow Wilson insisted that "there is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight," the sinking of the Lusitania and the death of 128 Americans planted the seed of war. It shifted the American psyche. Germany was no longer just a belligerent nation; it was a barbarian state. The sinking did not bring the US into the war immediately, but it made neutrality psychologically impossible.

Anatomy of a Cover-Up: The Munitions Conspiracy

Cargo Manifests and Contraband

For decades, the British government denied that the Lusitania was carrying anything other than passengers and harmless cargo. They lied.

The cargo manifest, now public, is a smoking gun. The ship was carrying 4,200 crates of Remington .303 rifle cartridges (over 4 million rounds) destined for the British Army. There were also 1,250 cases of empty shrapnel shells and 18 cases of fuses.

But the conspiracy runs deeper. The manifest lists tons of "butter," "cheese," and "oysters" that were never refrigerated. Researchers have long suspected that these were code words for highly volatile explosives like gun cotton or aluminum powder. Munitions on passenger ships violated the rules of the cruiser warfare the British expected the Germans to follow, making the Lusitania, in technical terms, a legitimate auxiliary cruiser.

The Second Explosion Theory Revisited

This brings us back to the forensic mystery of the second explosion. Modern simulations suggest that a single torpedo could not have sunk the ship in 18 minutes. The damage pattern suggests an internal detonation.

If the torpedo ignited the coal dust, it was a freak accident. But if the torpedo struck the magazine where the illicit munitions were stored, then the Lusitania was essentially a floating bomb. The British Admiralty’s frantic efforts to depth-charge the wreck in the years following the war suggest they had something to hide. They weren't just clearing a navigation hazard; they were erasing the evidence of a war crime—using civilians to protect military shipments.

The Wreck Below: A Dissolving Grave in the Celtic Sea

Lusitania Wreck Diving and the Hostile Environment

Unlike the Titanic, which lies in the pristine, oxygen-low depths of the mid-Atlantic, the Lusitania lies in a dynamic, hostile environment. She rests just 11 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale in 93 meters (305 feet) of water.

This is not a preserved museum piece. The water is murky, green, and filled with silt. The currents are vicious, capable of sweeping divers away. The wreck is draped in forgotten fishing nets—deadly curtains that snag equipment and trap the unwary.

Because of the depth and the environment, the ship has collapsed. She is flattened, "pancaked" by the weight of the water and the structural failure of her steel. The iconic four funnels are long gone, dissolved into rust. To dive the Lusitania is to visit a scrapyard in a sandstorm.

The Depth Charge Controversy

During World War II, the Royal Navy frequently dropped depth charges on the wreck of the Lusitania. The official explanation was that they were using the magnetic anomaly of the hull for target practice to train anti-submarine crews.

However, many historians and wreck divers view this with extreme skepticism. The damage to the wreck is consistent with heavy blasting designed to break up the hull. Was the Royal Navy trying to destroy the remaining munitions to prevent their discovery? The destruction has made forensic analysis of the "second explosion" area nearly impossible, sealing the secret in twisted metal.

Gregg Bemis: The Man Who Owned the Lusitania

For decades, the wreck was the private property of Gregg Bemis, an American venture capitalist who bought the salvage rights in the 1960s. Bemis spent the rest of his life in a legal war with the Irish government to obtain permits for Lusitania wreck diving.

Bemis was not a treasure hunter; he was a truth hunter. He wanted to cut into the hull to find the physical proof of the munitions that caused the second explosion. He believed that the British government framed the Germans for an atrocity that was, in part, a self-inflicted wound caused by reckless endangerment. Bemis died in 2020, never having fully unlocked the ship's final secrets, but his efforts kept the controversy alive.

Conclusion: The Death of Chivalry

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania was more than a maritime disaster; it was a distinct psychological break in the timeline of the 20th century. When the ship slipped beneath the waves at 2:28 PM on May 7, 1915, the "Gentleman’s War" ended. The 19th-century ideals of honor, restricted warfare, and the sanctity of civilian life were torpedoed alongside the ship.

It marked the transition to Total War—a conflict where the line between the soldier and the infant, the battleship and the ocean liner, was erased. Today, the wreck is dissolving. The steel is reverting to iron oxide, bleeding into the Celtic Sea. Soon, the physical evidence of the betrayal will be gone entirely, leaving only the story of a palace that sailed into a war zone, and the 1,198 souls who paid the price for the world's loss of innocence.

Sources & References

- National Geographic - "How one torpedo sank the mighty Lusitania"

- Imperial War Museums - "18 Minutes That Shocked The World"

- Library of Congress - "The Lusitania Disaster: Newspaper Pictorials"

- Archaeology Magazine - "Lusitania's Secret Cargo"

- Encyclopedia Britannica - "Lusitania: History, Sinking, Facts, & Significance"

- Stanford Magazine - "What Really Happened?" (Gregg Bemis & The Wreck)

- National Archives (US) - "Sinking of the RMS Lusitania: Pieces of History"

- National Museums Liverpool - "RMS Lusitania Archive Sheet"