The Dawn Watch

The first thing you notice is the sound. Before the sun has fully breached the smog-hazed horizon of Beijing, before the tourists have fully congregated, there is a rhythmic, mechanical percussion that strikes the pavement. It is the sound of ninety-six boots hitting the ground in perfect unison.

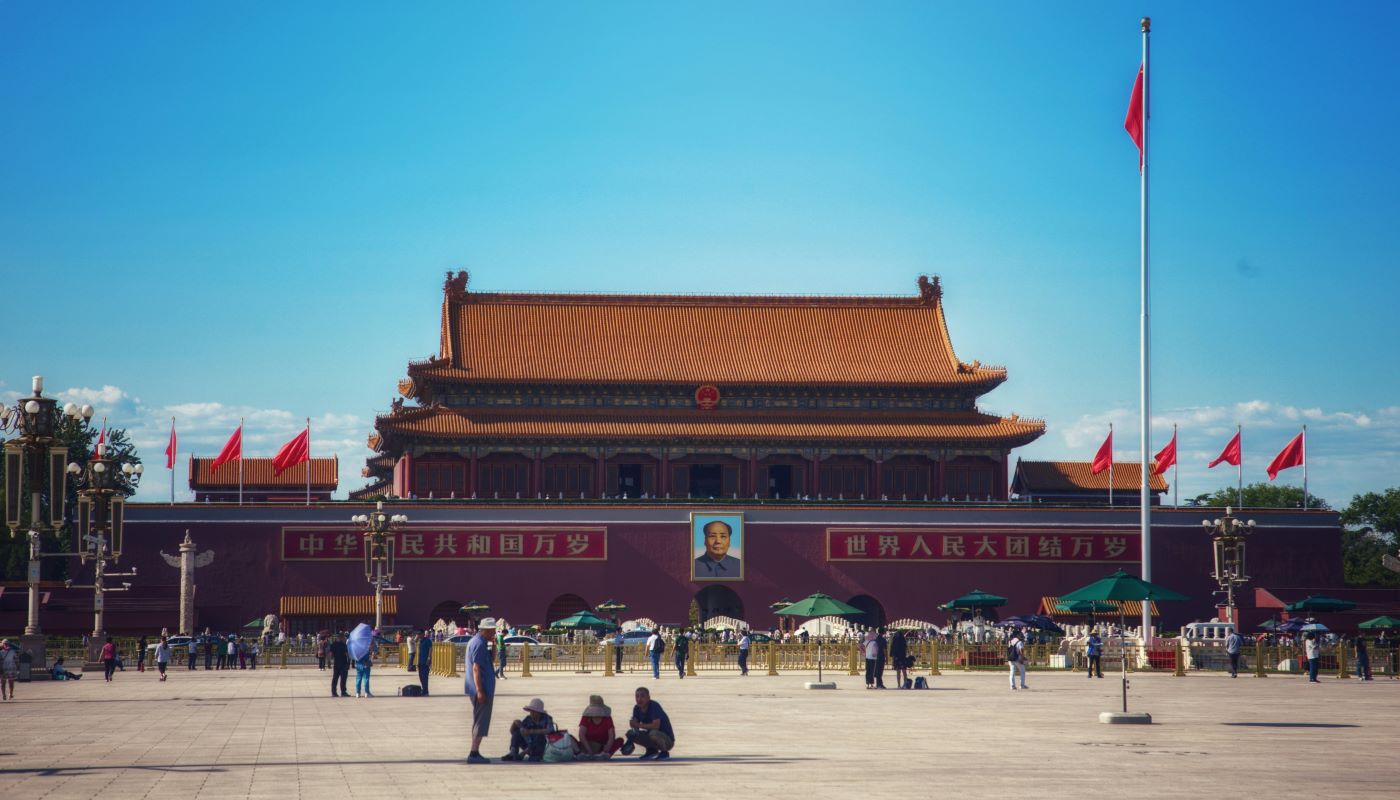

Standing in the center of Tiananmen Square at dawn offers a sensation that can only be described as intellectual vertigo. The air is often thick, carrying the metallic taste of the city, but the space itself is vast enough to create its own microclimate. As the Honor Guard of the People’s Liberation Army marches across the "Golden Water Bridges" and toward the flagstaff, the sheer scale of the environment begins to press down on you. This is not a town square in the European tradition—a cozy piazza designed for markets, gossip, and coffee. This is a 440,000-square-meter concrete tundra, an expanse so flat and so wide that it seems to curve with the earth itself.

As the heat begins to radiate off the granite paving stones, the psychological intent of the architecture becomes clear. You are not here to relax. You are here to witness. The square is a stage designed for the state, where the individual observer is rendered microscopic, a temporary speck of dust on a timeline of eternal governance. The flag rises, the anthem plays, and for a moment, the thousands of onlookers are silent, caught in the gravity of the Beijing central axis. But beneath the pomp and the camera shutters, there is a tension in the air—a collision of ancient geomancy, socialist realism, and the invisible, heavy weight of a history that is strictly forbidden to be spoken.

The Axis of Emperors: Geomancy and Geography

To understand the vertigo, one must understand the geometry. Tiananmen Square does not exist in isolation; it is the anchor of the historic north-south axis of Beijing, a line that has organized the capital’s cosmology for centuries. In imperial times, this axis represented the connection between the heavens and the earth, with the Emperor seated at the center, the conduit of celestial power.

Today, the square retains that geometric dominance but subverts its purpose. Where the ancient design utilized walls and courtyards to create layers of privacy and exclusivity for the Emperor, the modern square obliterates privacy entirely. It is an open plain. The axis that once guided the spirit of the dragon now guides the gaze of the state.

The scale is deliberate. It is roughly the size of 60 soccer fields, capable of holding 600,000 people—or, in more turbulent times, one million. Unlike Trafalgar Square in London or Red Square in Moscow, which retain a relationship with the surrounding urban fabric, Tiananmen feels severed from the city. It is an island of ideological purity. When you stand in the center, the city of Beijing—the noodle shops, the chaotic traffic, the messy vibrancy of life—feels miles away, pushed back by an invisible force field of stone and authority.

The Imperial Threshold: The Gate of Heavenly Peace

Domineering the northern edge of the square is the structure that gives the plaza its name: the Tiananmen, or Gate of Heavenly Peace. This is the Forbidden City entrance, the threshold between the mortal world of the commoner and the divine world of the Emperor. Its massive crimson walls and double-eaved roof of yellow glazed tiles are the ultimate symbols of dynastic authority.

However, the gate acts as a jarring historical pivot point. While the architecture screams of the Ming and Qing dynasties, the iconography is strictly Communist. The massive portrait of Mao Zedong hangs above the central tunnel, his gaze fixed permanently southward, watching over the square he transformed.

Passing through this gate is a rite of passage for domestic tourists, a reclamation of a space once forbidden to them. But for the historian or the aware traveler, the gate represents a complex duality. It is named for "Heavenly Peace," yet it has presided over some of the most violent upheavals in Chinese history. It is a beautiful, imposing facade that masks the deep contradictions of modern China—a fusion of imperial aesthetic and revolutionary dogma.

Concrete Tundra: The Maoist Transformation

The square we see today is not the square of the emperors. Originally, this space was a T-shaped imperial corridor, narrower and lined with government ministries, enclosed by walls. It was a bureaucratic passage, not a public gathering place.

The transformation began in the 1950s. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic, the Communist Party sought to create a monumental space that could rival Moscow’s Red Square, but on a grander scale. They envisioned a site for mass rallies, a place where the "masses" could physically manifest their support for the Party.

To achieve this, the old was obliterated. The narrow corridor was widened, the ministry buildings were demolished, and the ceremonial "Gate of China" was removed. In a move that stripped the area of any softness, trees were uprooted and benches were banned. The logic was utilitarian and paranoid: trees could hide assassins or obscure the view of the reviewing stand; benches would encourage loitering. The result was a sterile, paved desert. It is a landscape of hard edges and grey stone, a "concrete tundra" where there is no shade, no shelter, and nowhere to hide. It is socialist realism manifested in urban planning—the total subjugation of nature and the individual to the will of the collective.

The Mausoleum: A Pilgrimage to the Preserved

At the southern end of the square, countering the Gate of Heavenly Peace, sits the Mao Zedong Mausoleum. Entering this building is perhaps one of the most surreal experiences in the canon of Beijing dark tourism.

The queue often snakes around the building, thousands of people deep. The atmosphere in line is a mix of reverence, curiosity, and dutiful boredom. However, as you approach the entrance, the mood shifts. Security is tighter here than anywhere else. Hats must be removed. Hands must be taken out of pockets. Talking is hushed.

Inside, the air is cool and smells faintly of formaldehyde and the thousands of white chrysanthemums sold by vendors at the entrance. You are ushered into the central chamber, where the Great Helmsman lies in a crystal coffin. The body is draped in a red flag, bathed in strange, warm lighting designed to make the skin look flushed and vital. In reality, the preservation gives the face a waxy, doll-like sheen.

The paradox is palpable. Mao signed a proposal in 1956 that all central leaders should be cremated. He wished to return to the earth. Instead, he was embalmed against his will, turned into a permanent idol to anchor the legitimacy of the state. Walking past the coffin, you are not just looking at a corpse; you are looking at the physical embodiment of the Party’s refusal to let go of the past, even as it rewrites it.

The Architecture of Power: Flanking the Void

If the North-South axis represents the timeline of history, the East-West axis represents the crushing weight of the present bureaucracy. The square is flanked by two colossal structures that exemplify the Great Hall of the People architecture.

To the west lies the Great Hall of the People, the meeting place of the National People’s Congress. To the east is the National Museum of China. These buildings are designed as mirror images, utilizing a style often called "Sino-Soviet," which blends heavy, neoclassical columns with Chinese decorative motifs.

The scale of these buildings is designed to dwarf the human form. The pillars are too thick, the steps too wide, the facades too long. They act as bookends of authority, pressing in on the open space of the square. When you walk between them, you feel the intended effect: the State is massive, eternal, and immovable, while you are transient and small. The architecture does not invite participation; it commands submission.

The Stone Obelisk: Monument to the People’s Heroes

In the center of the vastness stands the Monument to the People’s Heroes, a ten-story obelisk of granite and marble. It is the focal point of the square, physically interrupting the sightline between Mao’s portrait and his mausoleum.

The base of the monument is adorned with white marble bas-reliefs depicting revolutionary struggles—the Opium Wars, the Jintian Uprising, the May Fourth Movement. The artistry is dynamic, depicting brave men and women rising up against oppression.

The irony of this monument is piercing. It celebrates the very act of protest and rebellion that is now strictly prohibited in the square surrounding it. It was here, at the steps of this monument, that students gathered in 1976 to mourn Zhou Enlai, and again in 1989 to demand reform. The monument was meant to canonize the revolutionary spirit, but today it sits in a zone where any spark of that spirit is extinguished by police intervention within seconds.

The Prelude to 1989: A City of Tents

To understand the atmosphere of the square today, one must confront the ghost that haunts it. This is the Tiananmen Square history that is scrubbed from the books but remains etched in the world’s memory.

In the spring of 1989, the concrete tundra was transformed. It ceased to be a sterile parade ground and became a living, breathing city of tents. For weeks, it was a festival of hope. Students, workers, and intellectuals occupied the square, setting up printing presses, medical stations, and art installations.

The defining image of this period was the "Goddess of Democracy," a 10-meter-tall statue constructed of foam and plaster over a metal armature. The students positioned her to face directly north, staring straight at the portrait of Mao on the Gate of Heavenly Peace. It was a spatial challenge—a fragile, temporary goddess confronting an eternal, authoritarian god. The air was electric with the belief that the sheer will of the people could reshape the geometry of power.

The Night of June Fourth: The Battle of Muxidi

The dream ended on the night of June 3rd and the early hours of June 4th. But to say the violence happened "in the square" is a misnomer that softens the reality. The true slaughter began kilometers to the west, along the approaches of Changan Avenue, specifically at the Muxidi Bridge.

At around 10:00 PM on June 3rd, the 38th Group Army arrived at the Muxidi intersection. They were met not by students, but by a massive wall of ordinary Beijing citizens—workers, retirees, and neighbors—who had used trolleybuses to block the road. Unlike previous weeks, where soldiers had been unarmed and hesitant, these troops were helmeted and carrying AK-47s loaded with expanding bullets.

The soldiers fired directly into the crowd. This was not warning fire; it was suppression. Eyewitnesses describe a scene of absolute confusion: citizens screaming "Fascists!" and throwing bricks, only to be cut down by automatic fire. The nearby Fuxing Hospital was quickly overwhelmed, its floors slick with blood, with bodies piled in bicycle sheds because the morgue was full.

By the time the armored personnel carriers (APCs) reached the square itself around 1:00 AM, the psychological conquest was complete. The lights in the square were cut, plunging the vast expanse into darkness. For the thousands of students huddled around the Monument to the People's Heroes, the sound of the tanks grinding over the barricades on Changan Avenue was the sound of the world ending.

The Toll: Numbers in the Fog

The exact death toll remains one of the most heavily guarded secrets of the Chinese Communist Party. Because bodies were cleared away by the military in the early hours of June 4th—some reportedly cremated on site or trucked away—an accurate count is impossible. However, we can triangulate the scale of the tragedy through various sources.

The Chinese government initially claimed near-zero civilian deaths, later adjusting the figure to 241 (including soldiers), labeling the victims as "rioters." This stands in stark contrast to the Chinese Red Cross, which estimated 2,600 deaths early on the morning of June 4th before being pressured to retract the figure. Declassified British diplomatic cables from the time cited a Chinese source estimating the toll as high as 10,000, while US intelligence documents have ranged from hundreds to nearly 3,000. Beyond the dead, it is estimated that 7,000 to 10,000 people were injured, many left with permanent disabilities.

The Tank Man: Symbolism and Mystery

The morning after the crackdown, June 5th, produced the most recognizable image of the 20th century. On Changan Avenue, just east of the square, a column of tanks was leaving the area. A lone man, wearing a white shirt and carrying shopping bags, walked out and stood in front of the lead tank.

The Tank Man symbolism lies in the asymmetry of the confrontation. It was soft flesh against hardened steel; the mundane grocery bags against the machinery of war; the individual against the collective state. For a few minutes, the man danced with the tank, moving left and right to block its path. He climbed onto the turret, spoke to the soldiers, and then climbed down. He was eventually pulled away by onlookers (or perhaps security agents). His identity remains unknown. His fate is a state secret.

The Consequences: The Great Bargain

The crackdown was not merely a tactical operation; it was the foundational moment of modern China, fundamentally altering the trajectory of the nation. In the immediate aftermath, a purge swept across the country. While student leaders were often jailed, the harshest punishments fell on the workers who had supported them. Thousands were arrested; many were executed after swift, televised trials. The reformist wing of the party was decapitated, with General Secretary Zhao Ziyang placed under house arrest until his death.

But the most profound consequence was the new, unspoken social contract that emerged in the years that followed: "We will make you rich, but you must remain silent."

The Party traded legitimacy for prosperity. They accelerated the shift to hyper-capitalism to ensure that the people were too busy making money to demand democracy. The idealism of the 1980s was replaced by the materialism of the 1990s and 2000s. The square, once a place of political possibility, became a tourist backdrop—a void where the only approved activity is to consume the view and obey the guards.

The Great Forgetting: Scrubbing the Stones

In the days following the crackdown, the square was closed. The physical cleanup was meticulous. Fire hoses were used to wash the blood and debris from the stones. The tank tracks were repaired. The bullet holes were patched.

But the psychological cleanup was even more thorough. The government constructed a narrative of "counter-revolutionary turmoil" that required a necessary intervention to restore order. Over the decades, even that narrative was quieted, replaced by total silence.

The "Great Forgetting" is the square’s most defining modern feature. The event has been erased from textbooks, media, and the internet. The square is now a void. When you walk there today, you are walking on a palimpsest where the bottom layer has been aggressively scraped away. The emptiness you feel is not just spatial; it is historical. It is a vacuum where memory should be.

The Panopticon: Cameras and Control

Today, Tiananmen Square is perhaps the most scrutinized patch of earth on the planet. As you walk the expanse, you will notice the "forest" of lamp posts. They are rectangular and grey, blending into the background, but look closely. Each post is laden with clusters of high-tech surveillance cameras.

This is the modern panopticon. These are not just video feeds; they are integrated with facial recognition software and AI behavioral analysis. If you stop for too long, if you unfurl a piece of fabric, if you raise your voice, you are flagged.

The feeling of being watched is visceral. It creates an Orwellian atmosphere where private conversation feels dangerous. The square is strangely quiet, not just because of its size, but because people instinctively lower their voices. The surveillance eliminates the potential for spontaneity. There are no street performers, no hawkers, no impromptu debates. There is only the approved movement of bodies through the approved channels.

Entering the Fortress: Tourist Logistics

Visiting Tiananmen Square today requires navigating a gauntlet of security that rivals an international airport. You cannot simply stroll in from the street. You must book a reservation in advance, often days ahead.

On the day of your visit, you will queue at one of the perimeter checkpoints. You must present your passport or national ID card. Your bags are X-rayed. You are patted down. This friction is deliberate. It filters the crowd and establishes the terms of the engagement: you are entering a secure facility, not a public park.

Once inside, you will notice the omnipresence of the "umbrella men"—plainclothes police officers who stand under sun umbrellas, watching the crowd. They are indistinguishable from tourists until you notice their earpieces and their alert, scanning eyes. They are the human element of the security grid, ready to intercept anyone who deviates from the script.

The Taboo: What Cannot Be Said

For the international visitor, there is a burden of knowledge. You enter the square knowing what happened, but you are also entering a zone where that knowledge is contraband. The Great Firewall prevents you from searching for "1989" or "Tank Man" on your phone while connected to local networks.

It is critical to understand the taboo. Do not ask your tour guide about the "incident." Do not try to discuss it with locals. Even if they know (which many older residents do), discussing it in public puts them at risk. For the younger generation, the ignorance is often genuine.

On the Chinese internet, the censorship is a constant game of cat and mouse. Netizens use code words like "May 35th" (May 31st + 4 days) to reference the date. But in the square itself, there is no room for code. The silence is enforced. To speak of the dead here is to commit a political act.

Nearby Contrast: The Hutongs

To escape the oppressive symmetry of the square, one only needs to walk a few blocks south into the Dashilar area and the remaining Hutongs. The contrast is jarring.

The Hutongs are the narrow, grey-brick alleys that formed the capillary system of old Beijing. Here, life is chaotic and human-scale. Laundry hangs from power lines. Old men play chess on low stools. The smell of frying dumplings and coal smoke fills the air.

This juxtaposition highlights the artificiality of Tiananmen. The Hutongs represent the organic, messy, uncontrollable reality of human life. Tiananmen represents the state’s desire to organize, sterilize, and control that life. Moving between the two is like moving between two different dimensions—one built for people, the other built for power.

The Golden Hour: Sunset and Clearance

As the sun sets, the square undergoes its final ritual of the day. The flag-lowering ceremony mirrors the dawn, drawing crowds to watch the Honor Guard retrieve the national symbol.

But immediately following this, the clearance begins. Unlike squares in other cities that come alive at night, Tiananmen is emptied. Police lines sweep across the vast pavement, herding tourists toward the exits. The square is not a place for evening strolls or lovers' trysts.

By nightfall, the square is a desolate, illuminated stage with no actors. The floodlights wash the Great Hall and the Gate in a golden glow, but the center is empty. It becomes a pure abstraction of order, secure and lifeless, guarded by the cameras that never blink.

The Visitor’s Burden

Standing in Tiananmen Square induces a specific kind of cognitive dissonance. You are surrounded by families taking selfies, children eating ice cream, and tour groups following flags. There is laughter and sunlight.

Yet, superimposed over this scene is the mental imagery of burning armored personnel carriers and crushed bicycles. You are seeing two squares simultaneously: the physical one before your eyes and the historical one in your mind. This is the intellectual vertigo. You feel the invisible weight of the events that occurred on these very stones, events that the people standing next to you may be completely unaware of.

It is a lonely feeling. You are a witness to a ghost that no one else acknowledges. You are walking through a graveyard that calls itself a celebration.

Conclusion: The Silence that Speaks

Tiananmen Square is a monument to the power of the state to rewrite reality. It is a triumph of engineering and social control, a place where the physical environment forces the individual into submission. The blood has been washed away, the bullet holes filled, and the history books redacted.

However, the emptiness of the square is, in itself, a monument. The frantic sterilization of the site betrays the state’s fear of memory. The void is not just an absence; it is a scar.

For the outsider, the act of visiting Tiananmen Square becomes an act of remembrance. By walking the "concrete tundra" and acknowledging the tragedy that occurred there, you deny the finality of the erasure. The tanks could crush the tents, and the censors can scrub the internet, but they cannot scrub the atmosphere. The silence of Tiananmen Square is loud. It speaks of a grief that has nowhere to go, hovering forever over the gate of heavenly peace.

Sources & References

- The Tiananmen Papers – Compiled by Zhang Liang, edited by Andrew J. Nathan and Perry Link. (Archival documents regarding the 1989 crackdown).

- The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited – Louisa Lim. (In-depth journalistic investigation into the memory of 1989).

- Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang – Zhao Ziyang. (First-hand account from the ousted General Secretary).

- Human Rights Watch – "1989 Tiananmen Massacre" reports and retrospectives.

- PBS Frontline: The Tank Man – Documentary investigating the identity and fate of the lone protester.

- The New York Times – "Tiananmen Square Massacre" Archival Coverage (June 1989).

- Amnesty International – Reports on censorship and surveillance in modern China.

- The Guardian – "Tiananmen Square: The Great Forgetting" (Feature articles).

- Stanford University – The Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989 (Digital Archive).

- Lonely Planet/Travel Guides – Current logistical requirements for visiting Tiananmen Square (Security protocols).