The View from the Blast Door: Entering the NORAD Command Center

The air inside the tunnel leading to the North Portal tastes of industrial exhaust and the cold, damp scent of crushed stone. You are standing under 2,000 feet of Precambrian granite, a weight that feels visceral, pressing against the crown of your skull. Before you sits the primary seal: a 25-ton steel blast door. It is three feet thick. It does not swing open with a cinematic hiss; it moves with a slow, grinding mechanical finality. When these doors close—a process that takes exactly 40 seconds—the world outside ceases to exist for the inhabitants within. This is not a workplace. It is a lifeboat for the architects of Armageddon.

Twenty-Five Tons of Steel and Silence

The threshold of the North Portal is the most heavily fortified entrance on the planet. The doors are designed to withstand a 30-megaton nuclear blast at close range. If a warhead were to detonate over Colorado Springs, the mountain would absorb the initial thermal radiation, but the door would take the overpressure. Behind the first door lies a second, identical 25-ton slab, creating a vacuum seal that prevents radioactive fallout from leaching into the internal air supply. Inside, the silence is thick. The granite walls, some of the hardest stone on earth, act as a natural acoustic dampener, swallowing the sound of footsteps. It is the silence of a tomb that is very much alive.

The Air of the Apocalypse: Life Inside the Mountain

The atmosphere within the complex is entirely artificial. It is scrubbed of particulates, pressurized to keep contaminants out, and cooled by massive industrial chillers that combat the heat generated by thousands of computer servers. You can hear the low, constant thrum of the 1,000-kilowatt generators. These engines are the heartbeat of the mountain. If the national power grid were to vanish in a pulse of electromagnetic interference, these generators would kick in instantly, drawing from a 1.5-million-gallon underground reservoir of diesel fuel. The smell is a sterile cocktail of ozone, floor wax, and recycled oxygen—the scent of a civilization that has retreated into the earth to wait out its own destruction.

Architects of the End Times: The Cold War Origins of Cheyenne Mountain

The mountain was not born of curiosity, but of pure, existential terror. In the late 1950s, the United States military realized that the sky was no longer a barrier. The advent of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) meant that a Soviet strike could reach the American heartland in less than 30 minutes. The previous command center at Ent Air Force Base was a "soft" target—a series of vulnerable brick buildings that would have been vaporized in the opening seconds of a conflict. To survive, the "brain" of American defense had to go deep.

The Sputnik Shockwaves and the Need for NORAD

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in October 1957, it was not just a scientific achievement; it was a military ultimatum. If the Russians could put a satellite in orbit, they could put a warhead on Washington. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was formalized in 1958 as a binational agreement between the U.S. and Canada. However, a command center is useless if its occupants are dead. The search for a "hardened" site led engineers to the front range of the Rockies. Cheyenne Mountain was chosen because it is composed of massive, monolithic granite, providing the ultimate natural armor against the escalating yields of Soviet hydrogen bombs.

Hollowed Granite: The Engineering of 1961

The excavation began in May 1961, a period of peak geopolitical tension. Over the next three years, mining crews used precision blasting to remove 693,000 tons of rock. This was not just a hole in the ground; it was a three-dimensional grid of intersecting caverns. The main chambers are 100 feet wide and 60 feet high. Inside these voids, engineers constructed 15 separate buildings. These structures are not attached to the mountain walls. They are freestanding steel boxes, separated from the granite by an 18-inch gap. This allows the buildings to move independently of the mountain, a necessary feature when the ground begins to liquefy under the stress of a nuclear ground-burst.

Chronology of the Cold Watch: A History of Near-Misses

The history of Cheyenne Mountain is a timeline of watching the radar and praying for a blank screen. From the moment it became operational in April 1966, the complex has been the focal point of global surveillance. It has processed billions of data points, from weather balloons to the frantic signatures of missile tests. But the mountain’s history is also defined by the moments when the machines lied.

Operation Sky Shield and the DEW Line Integration

In its early years, Cheyenne Mountain was the central nervous system for the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, a string of radar stations stretching across the Arctic Circle. The mountain processed the "raw" data from these remote outposts, turning blips into trajectories. Operation Sky Shield tested this integration, grounding all civilian aircraft in North America to simulate a total defense posture. The mountain proved it could track every moving object in the hemisphere, but the sheer volume of data created a new kind of danger: the risk of human or mechanical misinterpretation.

False Alarms and the Brink of Nuclear Fire

The mountain’s most terrifying hours occurred on November 9, 1979, and again in June 1980. In the first instance, a technician inadvertently loaded a "war games" simulation tape into the live system. For several minutes, the screens in the Combat Operations Center showed a massive, synchronized Soviet launch. Launch crews were put on high alert, and the "Kneecap" (the President’s National Emergency Airborne Command Post) was readied for takeoff. In 1980, a failing forty-six-cent computer chip began reporting random numbers of incoming missiles. In both cases, the mountain’s staff had to decide—within seconds—whether the world was ending or the computer was failing. They chose correctly, but the margin of survival was thinner than the paper the reports were printed on.

The Post-9/11 Pivot and Domestic Surveillance

On September 11, 2001, the mountain’s gaze flipped 180 degrees. For decades, NORAD looked outward, toward the poles, anticipating a Russian bomber or missile. When the towers fell, the threat was already inside the borders. The mountain’s role shifted toward Operation Noble Eagle, monitoring domestic air traffic for hijacked commercial flights. The "External Threat" model was dead. The mountain became the primary coordinator for the FAA and the military, turning its massive computational power toward the very heart of the nation it was built to protect.

The Mechanics of Survival: Engineering a Nuclear-Hardened Fortress

Cheyenne Mountain is a masterclass in survival physics. It is designed to withstand the physical effects of a nuclear explosion—not just the heat, but the ground shock, the electromagnetic pulse (EMP), and the biological fallout. To enter the mountain is to step into a machine designed to function while the rest of the world’s infrastructure is pulverized.

Suspended on Springs: The Physics of Ground Shock

The fifteen buildings inside the mountain sit on a forest of 1,311 massive steel springs. Each spring weighs roughly 1,000 pounds and is designed to support the weight of a three-story steel building. This is the mountain’s most critical defense mechanism. During a nuclear strike, the granite of Cheyenne Mountain would ripple like a liquid. The "ground shock" would shatter any structure bolted directly to the rock. These springs allow the buildings to sway up to 12 inches in any direction, absorbing the kinetic energy and keeping the delicate computer arrays and human operators from being crushed by the mountain's own movement.

The Sociology of the Bunker: Life in Zulu Time

There are no windows in Cheyenne Mountain. There is no sun, no rain, and no sense of the passing day. Personnel work under the harsh glow of fluorescent lights, governed entirely by Zulu Time (UTC). This creates a unique psychological phenomenon known as "bunker fatigue." Staff members often report a total loss of time perception, relying on the scheduled cafeteria meals to know if it is morning or night. The air is filtered through a redundant series of High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) and chemical-biological-radiological (CBR) filters. You are breathing air that has been stripped of the world, a sterile oxygen mix that keeps the brain sharp but leaves the spirit hollow.

The EMP Shield: Protection Against the Invisible Pulse

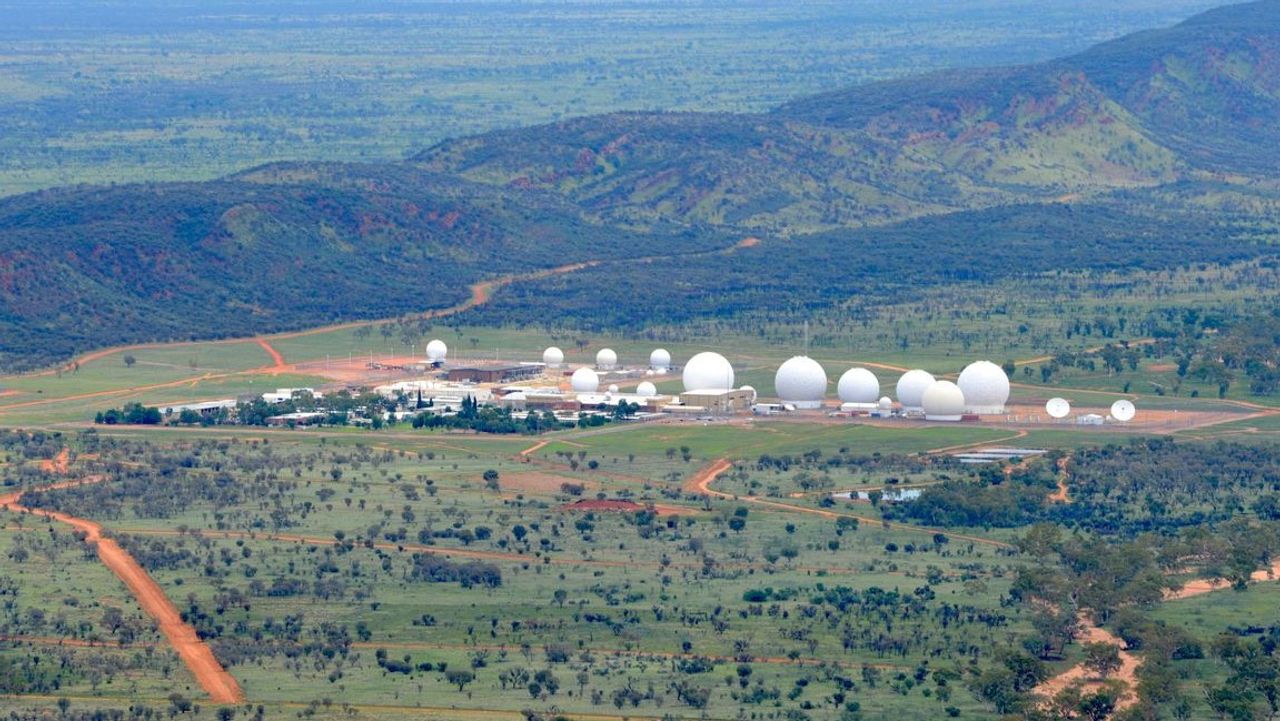

A nuclear detonation in the upper atmosphere generates an Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) that can fry every unshielded circuit for thousands of miles. To counter this, every building within the complex is essentially a Faraday Cage. The steel hulls are welded together to ensure electrical continuity, preventing the pulse from penetrating the interior. All power and data cables entering the mountain are fitted with massive surge protectors. In a total-war scenario, the mountain would be the only electronic "island" left functioning in a continent-sized graveyard of dead technology. This hardened electronic isolation makes the mountain the only reliable destination for the data streams flowing from Pine Gap in the Australian Outback. While the Australian facility serves as the "outer ear" capturing signals across the Eastern Hemisphere, Cheyenne remains the "brain" that processes that intelligence while the rest of the world’s grid turns to slag.

The Ghost in the Mountain: The Legacy of a Cold War Icon

In the 21st century, the mountain has become something of a paradox. It is both an active military asset and a relic of a previous era’s nightmares. While the primary day-to-day operations moved to Peterson Air Force Base in 2006, the mountain remains in "warm standby," ready to take the reins of the nation’s defense at a moment's notice.

From Active Command to Warm Standby

The move to Peterson was a matter of cost and convenience, but the mountain was never abandoned. In recent years, the threat of cyberwarfare and the development of hypersonic missiles by Russia and China have renewed the mountain’s relevance. You cannot "hack" a mountain that is physically disconnected from the public internet. The "warm standby" status ensures that the complex is fully staffed and the systems are running 24/7. It is the ultimate insurance policy. If the "soft" targets on the surface are compromised, the mountain wakes up. It functions as the heavy-metal counterpart to the Greenbrier Bunker in West Virginia; where Greenbrier was designed to preserve the legislative "heart" of the government, Cheyenne was built to protect the military "fist." Both sites represent a singular, desperate architecture of continuity—a plan to keep the state alive even after the citizenry has been vaporized.

Pop Culture and the Myth of the Stargate

The public’s perception of Cheyenne Mountain has been irrevocably altered by fiction. The 1983 film WarGames and the long-running Stargate SG-1 television series transformed this grim nuclear vault into a place of wonder and adventure. In the basement of the complex, there is even a door labeled "Stargate Command"—a piece of self-aware military humor. However, this pop-culture veneer masks the site's true, dark purpose. The mountain was never about exploring the stars; it was about ensuring that if the earth burned, someone would be left to witness the fire.

Entering the Granite Ribs: The Dark Atlas Visit Entry

Visiting Cheyenne Mountain is not a matter of buying a ticket. It is an exercise in bureaucratic endurance. Because it remains an active-duty military installation (the Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station), access is strictly controlled. Most visitors never get past the North Portal. To step inside is to be granted a temporary seat at the end of the world.

Logistics of the Restricted Zone: Securing Entry

For the investigative journalist or the authorized visitor, the process begins months in advance with a National Agency Check. You are vetted, screened, and cleared before you even set foot in Colorado. Once at the gate, your electronics are confiscated. No cameras, no phones, no recording devices. You are stripped of your digital tether to the outside world. The transport into the mountain is via a specialized military bus, driving through a tunnel that feels increasingly claustrophobic as the granite arches over you.

The Weight of the Granite: A Psychological Deep-Dive

Standing in the "Cathedral"—the largest of the excavated chambers—is an experience of profound insignificance. The scale of the engineering is a testament to human ingenuity, but the purpose of that engineering is a testament to human failure. You are surrounded by millions of tons of rock that were hollowed out because we could not figure out how to live together on the surface. The air is cold, roughly 60 degrees Fahrenheit, and the lack of natural light creates an immediate, low-level anxiety. It is the realization that if the doors ever close for real, everyone you love on the outside is already gone.

The Ethics of the Bunker: The Great Divorce

There is a moral heaviness to Cheyenne Mountain. It represents the "Great Divorce" between the state and the citizenry. In a nuclear exchange, the mountain would protect the generals, the data, and the command structure, while the population they serve would be left to the elements. Standing inside, you feel the hollow silence of a site that was built to survive a tragedy it cannot prevent. It is a monument to the Mutually Assured Destruction doctrine—a billion-dollar fortress built on the hope that its primary functions will never, ever be used.

FAQ: Essential Facts About the Cheyenne Mountain NORAD Bunker

What is the primary purpose of the Cheyenne Mountain Complex?

The Cheyenne Mountain Complex serves as a nuclear-hardened command and control center for the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and the United States Space Force. Its primary function is to provide the President and military leaders with a survivable facility from which to monitor aerospace threats, including incoming intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and to coordinate a national response during a nuclear war.

Where is the Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station located?

The facility is located in Colorado Springs, Colorado, within the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The bunker itself is situated 2,000 feet beneath the summit of Cheyenne Mountain, providing a natural armor of Precambrian granite that is among the hardest rock formations on earth.

Is Cheyenne Mountain still active after the move to Peterson?

Yes. While many day-to-day administrative functions moved to Peterson Space Force Base in 2006, Cheyenne Mountain remains in a warm standby status. It is fully operational 24/7, maintaining a crew of over 300 personnel who ensure that the facility can assume full command of North American defense at a moment's notice should surface installations be compromised.

Can the public tour the NORAD facility at Cheyenne Mountain?

No. Due to its status as an active-duty military installation and its critical role in national security, Cheyenne Mountain is closed to the general public. Tours are extremely rare and are typically reserved for government officials, military personnel, and vetted members of the media.

How does Cheyenne Mountain survive an electromagnetic pulse (EMP)?

The entire facility is built as a series of Faraday Cages. The 15 buildings inside the mountain are constructed from half-inch thick steel plates that are welded together to form a continuous electrical shield. This prevents the high-voltage surge of an EMP from reaching the delicate computer systems inside, ensuring the complex remains operational even if the national power grid is destroyed.

Sources and Citations

- Cheyenne Mountain Complex Official Overview - NORAD Public Affairs (2023)

- The Evolution of NORAD: From Cold War to Cyber War - U.S. Department of Defense (2021)

- Engineering a Mountain: The 1961 Excavation Records - American Society of Civil Engineers Archives (1966)

- Seismic Design of Hardened Facilities - Federal Emergency Management Agency Technical Library (2018)

- Pine Gap and the Global Surveillance Network - Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability (2017)

- Project Greek Island: The Greenbrier Bunker History - The Greenbrier Historical Archives (2022)

- The Sociology of Underground Habitats - Smithsonian Institution Historical Division (2019)

- US Space Force Station Cheyenne Mountain Status Report - United States Space Force (2024)