The City Beneath the City

Beneath the romantic boulevards and grand monuments of Paris lies another world—a dark, winding labyrinth of tunnels lined with the bones of six million people. The Paris Catacombs are not just a tourist attraction; they are a monument to the city’s forgotten dead, a testament to the way Paris has grown and changed over centuries, and a reminder of the fragility of human life. This is not just a place of bones; it is a place of stories—of revolution, of plague, of love and loss, and of the people who once walked the streets above.

The Catacombs began as a practical solution to a problem: what to do with the overflowing cemeteries of 18th-century Paris. But they became something more—a place where the past and present collide, where the dead seem to whisper to the living, and where the city’s hidden history is written in skulls and femurs. To walk through the Catacombs is to walk through time, to confront the reality of death, and to understand how a city remembers—and forgets—its dead.

The Birth of the Catacombs: A Crisis of the Dead

The Overcrowded Cemeteries of Paris

By the late 18th century, Paris was facing a crisis. Its cemeteries, particularly the massive Les Innocents cemetery in the heart of the city, were overflowing. Bodies were buried in shallow graves, stacked on top of one another, and often left to decompose in the open air. The stench was unbearable, and the risk of disease was constant. The situation came to a head in 1780, when the basement wall of a house adjacent to Les Innocents collapsed, spilling rotting corpses into the cellar.

The city needed a solution—and fast. The answer lay beneath the streets, in the vast network of tunnels left behind by the limestone quarries that had supplied the stone for Paris’s grand buildings. These tunnels, some dating back to Roman times, stretched for miles beneath the city. It was decided that the bones of the dead would be moved there, creating the world’s largest ossuary.

The First Transfers

The first transfers began in 1786, under the cover of night. Processions of priests and workers carried the bones from Les Innocents to the quarries, where they were carefully stacked in the tunnels. The work was done with reverence—each bone was treated as a sacred relic, and the workers often paused to pray for the souls of the dead.

By 1788, the transfer was complete. The bones of over two million Parisians had been moved to the tunnels, which were then consecrated as the "Paris Municipal Ossuary." But this was only the beginning. Over the next decades, as more cemeteries were closed, more bones were added to the Catacombs. By the mid-19th century, the tunnels held the remains of over six million people—a quarter of the city’s population at the time.

The Catacombs Today: A Journey Through the Underworld

Entering the Empire of Death

To visit the Catacombs today is to descend into another world. The entrance, a small green door on Place Denfert-Rochereau, gives little hint of what lies beneath. A narrow staircase leads down into the tunnels, where the air is cool and damp, and the only light comes from dim electric bulbs.

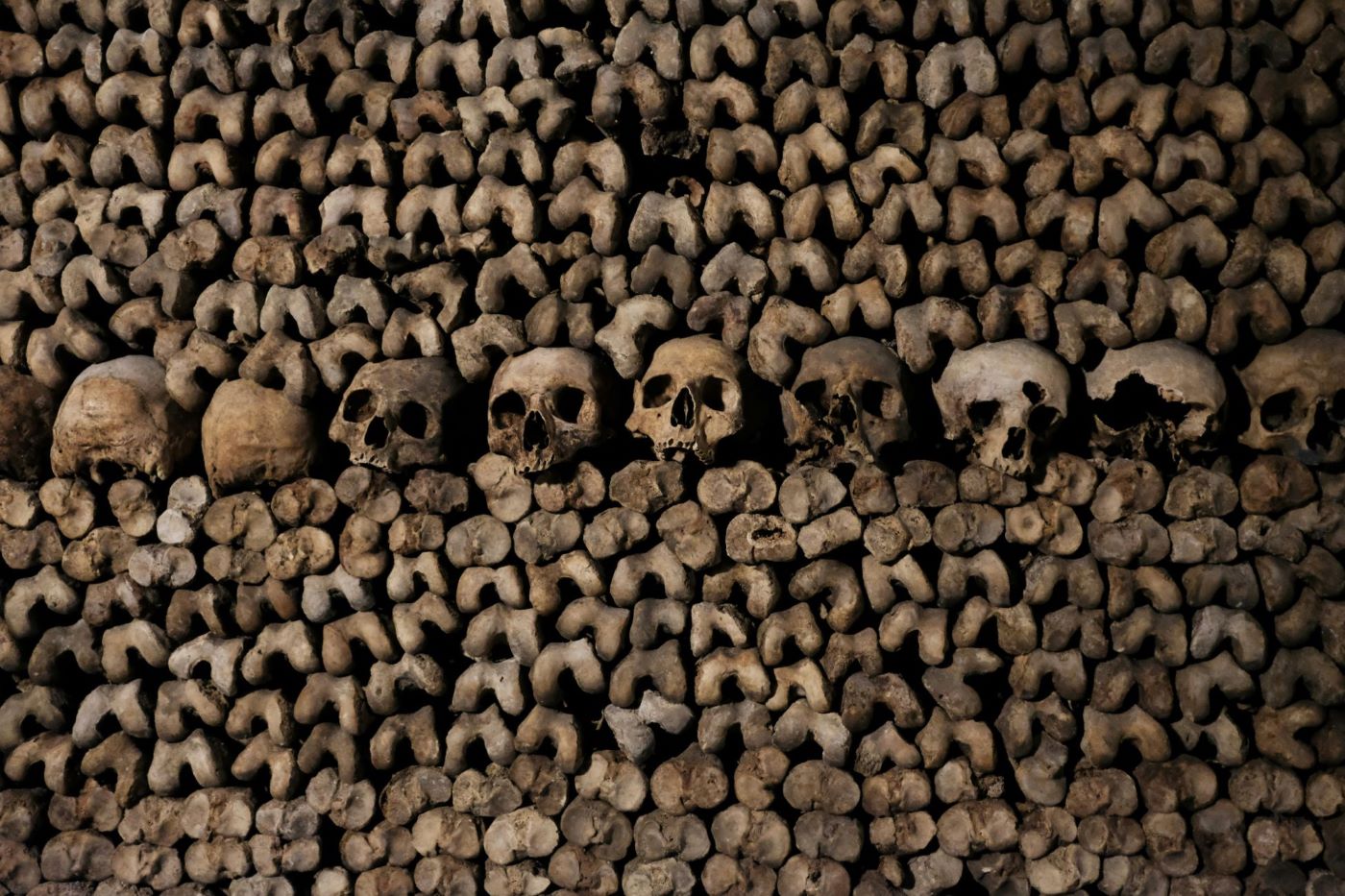

The first part of the tour takes visitors through the quarries themselves—narrow tunnels where the limestone was mined, their walls marked with the graffiti of 18th-century workers. Then, suddenly, the ossuary begins. Walls of bones stretch into the darkness, arranged with eerie precision. Skulls grin from the shelves, femurs and tibias stacked like cordwood. In some places, the bones are arranged into patterns—a heart made of skulls, a barrel shaped from femurs. In others, they are simply piled high, a testament to the sheer number of dead.

The Barrel of the Passion

One of the most striking features of the Catacombs is the Barrel of the Passion, a cylindrical pillar made entirely of bones, with a cross on top. It stands in a small chapel, where visitors often leave candles and flowers. The barrel is a reminder of the religious significance of the Catacombs—not just a storage place for bones, but a sacred site where the dead are remembered.

Nearby, a plaque bears an inscription from 1810:

"Arrête, c’est ici l’empire de la Mort"—"Stop, this is the empire of Death."

The Lost in the Labyrinth

The Catacombs are vast—over 300 kilometers of tunnels stretch beneath Paris, though only a small section is open to the public. Over the years, many have tried to explore the forbidden parts of the tunnels, sometimes with tragic results. In 1793, a man named Philibert Aspairt, a doorkeeper at the Val-de-Grâce hospital, entered the tunnels and never returned. His body was found 11 years later, near an exit he had somehow missed. His skeleton is now part of the Catacombs, a grim reminder of the dangers of the labyrinth.

In the 19th century, the Catacombs became a place of fascination for Parisian high society. Wealthy Parisians would host underground dinner parties in the tunnels, surrounded by the bones of the dead. The writer François-René de Chateaubriand described the Catacombs as "a place where one can dream of death without fear."

The Forgotten Stories: Who Lies Beneath Paris?

The Plague Victims

Many of the bones in the Catacombs belong to the victims of Paris’s many plagues. The Black Death struck the city repeatedly, from the 14th to the 17th centuries, each time leaving thousands dead. The bones of these victims were among the first to be transferred to the Catacombs, a final resting place for those who had died in agony.

One of the most devastating outbreaks was the plague of 1668, which killed over 40,000 Parisians. The bones of these victims were moved to the Catacombs in the 18th century, their identities lost to time.

The Revolution’s Dead

The Catacombs also hold the bones of those who died during the French Revolution. The cemeteries of Paris were filled with the victims of the guillotine, the battles in the streets, and the prisons where thousands perished. When the cemeteries were emptied, the bones of revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries alike were moved to the tunnels, their political differences forgotten in death.

Among them may be the remains of the Swiss Guards who died defending the Tuileries Palace in 1792, or the victims of the September Massacres, when over 1,000 prisoners were slaughtered in a single week. Their bones are anonymous now, but their presence is a reminder of the violence that once tore Paris apart.

The Unknown Dead

Most of the bones in the Catacombs are anonymous. They belong to the poor, the sick, the forgotten—those who died in Paris’s hospitals and workhouses, whose bodies were buried in mass graves. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Paris was a city of extreme inequality, and the Catacombs are a testament to the lives of those who were buried without ceremony, their names lost to history.

But among the anonymous dead are also the bones of the rich and powerful. When the cemeteries were emptied, the bones of nobles and bourgeoisie were moved to the Catacombs alongside those of the poor. In death, as in life, Paris was a city of contrasts—but in the Catacombs, all are equal.

The Catacombs in Myth and Legend

The Phantom of the Catacombs

Over the years, the Catacombs have inspired countless stories of ghosts and hauntings. One of the most famous is the legend of the Phantom of the Catacombs, a spectral figure said to wander the tunnels, weeping for the dead. Some claim it is the ghost of Philibert Aspairt, the doorkeeper who lost his way in the labyrinth. Others say it is the spirit of a plague victim, still searching for peace.

Visitors and workers in the Catacombs have reported strange occurrences—footsteps when no one is there, cold spots in the tunnels, and the sound of whispering voices. Some believe the Catacombs are haunted by the souls of the dead, still lingering in the place where their bones were laid to rest.

The Secret Societies

The Catacombs have long been a place of fascination for secret societies and underground cultures. In the 19th century, a group called the "Cataphiles" emerged—explorers who ventured into the forbidden parts of the tunnels, mapping them and leaving behind graffiti and installations. Some Cataphiles see the tunnels as a kind of underground kingdom, a world apart from the Paris above.

In the 20th century, the Catacombs became a haven for artists, rebels, and those who wanted to escape the constraints of society. During World War II, the French Resistance used the tunnels to hide from the Nazis. In the 1960s and 70s, the Catacombs were a gathering place for counterculture movements, who saw them as a symbol of freedom and defiance.

The Underground Cinema

In the 1950s, a group of French filmmakers known as the "Underground Cinema" movement began using the Catacombs as a setting for their avant-garde films. The tunnels, with their eerie atmosphere and labyrinthine layout, provided the perfect backdrop for stories of horror, surrealism, and existential dread.

One of the most famous films shot in the Catacombs was Les Yeux sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face), a 1960 horror film directed by Georges Franju. The film’s climactic scene, set in the Catacombs, has become iconic, and the tunnels have since appeared in countless other films, from The Phantom of the Opera to As Above, So Below.

The Dark Side of the Catacombs: Crime and Mystery

The Catacombs as a Hiding Place

The Catacombs have long been a refuge for those on the wrong side of the law. In the 19th century, criminals and fugitives would hide in the tunnels, knowing that the police were reluctant to venture into the labyrinth. Smugglers used the Catacombs to move contraband through the city, and counterfeiters set up hidden workshops in the tunnels.

During World War II, the Catacombs became a hiding place for Resistance fighters and Jews fleeing the Nazis. The tunnels provided a way to move undetected through the city, and some of the hidden chambers were used as safe houses.

The Unsolved Mysteries

The Catacombs have also been the site of numerous unsolved mysteries. In the 19th century, a series of murders were attributed to a killer known as the "Phantom of the Catacombs," who was said to lure victims into the tunnels and leave their bodies among the bones. The killer was never caught, and the murders remain unsolved.

In the 20th century, the Catacombs became a dumping ground for bodies. In the 1940s, the bones of Resistance fighters executed by the Nazis were hidden in the tunnels. In the 1980s, a man’s skeleton was found in a remote part of the Catacombs, dressed in 19th-century clothing. No one knows who he was or how he died.

The Modern Cataphiles

Today, the Catacombs are still explored by a subculture of urban explorers known as Cataphiles. These adventurers venture into the off-limits parts of the tunnels, mapping them, leaving behind graffiti, and sometimes even creating underground art installations.

The Cataphiles see the Catacombs as a kind of parallel world, a hidden city beneath the city. But their explorations are not without risk. The tunnels are unstable in places, and it is easy to get lost. Over the years, several Cataphiles have died in the Catacombs, their bodies found weeks or even years later.

The Catacombs in Literature and Art

The Romantic Era

In the 19th century, the Catacombs became a subject of fascination for Romantic writers and artists, who saw them as a symbol of the sublime—the intersection of beauty and terror. The French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote of the Catacombs as a place where "death and beauty are one."

The painter Eugène Delacroix visited the Catacombs and was inspired to create a series of sketches and paintings depicting the tunnels and their macabre decorations. His work captured the eerie beauty of the Catacombs, and helped to cement their place in the popular imagination.

The Surrealists

In the 20th century, the Surrealists were drawn to the Catacombs as a place where the boundaries between reality and dream were blurred. The artist André Breton, a founder of the Surrealist movement, explored the tunnels and wrote of them as a place where "the real and the imaginary are one."

The photographer Brassai captured the Catacombs in a series of haunting images, which were later published in his book Paris by Night. His photographs revealed the Catacombs as a place of mystery and beauty, where the past and present seemed to coexist.

The Catacombs in Modern Culture

The Catacombs continue to inspire artists and writers today. They have appeared in novels, films, and video games, often as a setting for horror or fantasy stories. The tunnels have become a metaphor for the hidden, the forgotten, and the uncanny—a place where the rules of the world above do not apply.

In recent years, the Catacombs have also become a subject of academic study. Historians and archaeologists have begun to explore the tunnels in earnest, seeking to understand the lives of the people whose bones line the walls. New technologies, such as 3D scanning and DNA analysis, are being used to map the Catacombs and to identify the remains of the dead.

The Ethical Questions: Respecting the Dead

The Catacombs as a Sacred Site

For all their fascination, the Catacombs are first and foremost a place of the dead. The bones that line the tunnels are not just decorations—they are the remains of real people, who lived and died in Paris. As such, the Catacombs raise important ethical questions about how we treat the dead, and how we remember them.

Some argue that the Catacombs should be treated as a sacred site, a place of mourning and reflection. Others see them as a historical artifact, a testament to the city’s past. The debate over how to balance these perspectives is ongoing, and it is a debate that touches on deeper questions about memory, history, and the meaning of death.

The Impact of Tourism

The Catacombs are one of Paris’s most popular tourist attractions, drawing over 300,000 visitors each year. But the influx of tourists has raised concerns about the impact on the site. The bones are fragile, and the constant flow of visitors risks damaging them. There are also questions about the appropriateness of turning a place of the dead into a tourist attraction.

In recent years, the city of Paris has taken steps to protect the Catacombs, limiting the number of visitors and restricting access to certain areas. But the debate over how to balance preservation with accessibility continues.

The Voices of the Dead

Perhaps the most important question raised by the Catacombs is this: what do we owe the dead? The bones in the tunnels are not just relics—they are the remains of people who had lives, families, and stories. Do we have a responsibility to remember them? And if so, how?

Some visitors to the Catacombs leave offerings—flowers, candles, or notes—on the walls of bones. Others simply pause to reflect on the lives that were lived above. In a city as bustling and modern as Paris, the Catacombs offer a rare moment of quiet, a chance to confront the reality of death and to remember the people who came before us.

Visiting the Catacombs: What You Need to Know

Practical Information

The Catacombs are open to the public year-round, though the number of visitors is limited. Tickets can be purchased online or at the entrance, and guided tours are available in several languages. The tour takes about 45 minutes and covers a small section of the tunnels. Visitors should be prepared for a cool, damp environment and should wear comfortable shoes, as the tunnels can be slippery.

It is important to note that the Catacombs are not recommended for those who are claustrophobic or who have mobility issues. The tunnels are narrow and uneven, and there are no elevators or wheelchair access.

The Rules of the Catacombs

The city of Paris has strict rules for visitors to the Catacombs:

- Do not touch the bones. They are fragile and irreplaceable.

- Do not take photographs with flash. The light can damage the bones.

- Do not wander off the marked path. The tunnels are easy to get lost in, and some areas are unsafe.

- Do not leave any offerings or graffiti. The Catacombs are a historical site and should be treated with respect.

Beyond the Catacombs: Other Hidden Paris Sites

For those fascinated by the hidden history of Paris, there are other sites worth exploring:

- The Sewers of Paris: A network of tunnels that tell the story of the city’s sanitation history.

- The Underground Rivers: The Bièvre and Seine rivers, which once flowed above ground but are now hidden beneath the streets.

- The Hidden Passages: The covered arcades of the 19th century, which were once the shopping malls of Paris.

- The Pere Lachaise Cemetery: The final resting place of Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, and many other famous figures.

Each of these sites offers a different perspective on the hidden history of Paris, and together they paint a picture of a city that is far more complex than its postcard image.

The Catacombs as a Mirror of Paris

The Catacombs are more than just a tourist attraction. They are a mirror of Paris itself—a city that is beautiful and brutal, glamorous and grim. The bones in the tunnels are a reminder of the millions of people who have lived and died in Paris over the centuries, whose stories are often forgotten in the rush of modern life.

In a way, the Catacombs are a metaphor for history itself. They are a place where the past is preserved, but also where it is hidden—buried beneath the surface, out of sight and out of mind. To visit the Catacombs is to confront this reality, to acknowledge the presence of the past in our present, and to remember that every city has its hidden layers.

In the end, the Catacombs are not just a place of bones. They are a place of stories—of the people who lived and died in Paris, of the city’s hidden history, and of the way the past and present are always intertwined. To walk through the Catacombs is to walk through time, to confront the reality of death, and to understand that the city above is built on the bones of those who came before.

References

- Kemp, R. (2011). The Catacombs of Paris: A Guide to the Empire of Death. McFarland.

- Arlette Farge (1993). Fragile Lives: Violence, Power, and Solidarity in Eighteenth-Century Paris. Harvard University Press.

- Guillemin, G. (2005). Les Catacombes de Paris: Histoire d'un autre monde. Parigramme.

- The Guardian. (2018). The Catacombs of Paris: A Journey into the Empire of Death. theguardian.com

- Paris Catacombs Official Site. (2021). History and Visitor Information. catacombes.paris.fr